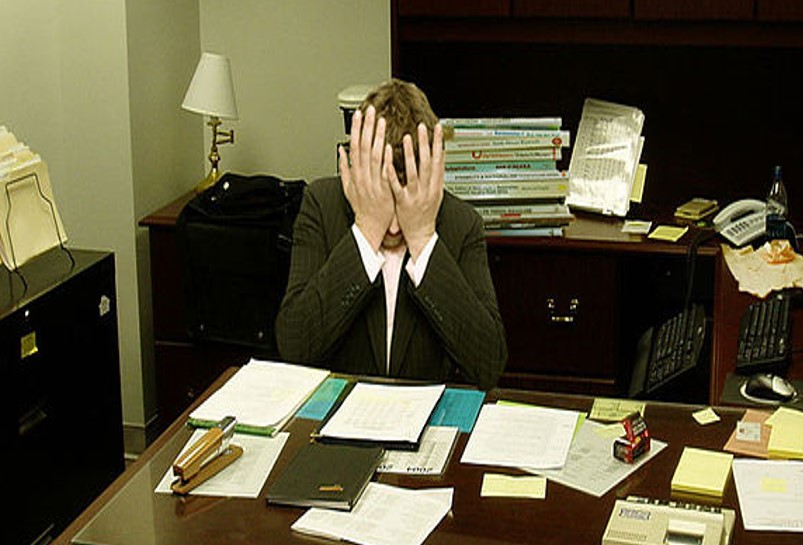

We’ve all been there. We gave them instructions, we answered their questions and we told them over and over again what to do… and then some of the work students hand in makes us want to pull our hair out. Why can’t they just do it? What didn’t they understand?

Why can’t they just do it? (Image: Wikipedia)

This blog post addresses how we can clearly communicate and transfer knowledge regarding assessment, especially written work.

Blind Experts

As instructors, we usually think we have given instructions and made our expectations known in the clearest way possible. Unfortunately, we are often too close to the task at hand to recognise that while something may be abundantly clear to us, it may not be so clear to others. It’s called expert blindness: when we are not aware of the knowledge and techniques we possess and employ in a particular field that allow us to carry out a range of tasks, such organising, evaluating and analysing information. As instructors we can forget how much we know, and that the students are still learning skills and knowledge, as well as how to integrate and apply the two.

If our goal is to help students become more expert-like in whatever topic/task/skill we are teaching them, then we need to give them opportunities for repeated practice (after all, you didn’t learn how to drive a car in one lesson). For practice to  be useful and meaningful, our expectations need to be as clear as possible. The use of grading rubrics containing the criteria and standards for assessment increases consistency and accountability, and is also beneficial for communicating standards and requirements to students. But what happens when you give students ‘clear’ instructions and include a rubric, and their work is still not what you anticipate?

be useful and meaningful, our expectations need to be as clear as possible. The use of grading rubrics containing the criteria and standards for assessment increases consistency and accountability, and is also beneficial for communicating standards and requirements to students. But what happens when you give students ‘clear’ instructions and include a rubric, and their work is still not what you anticipate?

Explicit and Tacit Knowledge

Grading rubrics are great for facilitating explicit knowledge transfer to students about their assessment. Explicit knowledge can (should!) be clearly and unambiguously expressed and received by all parties. Problems can arise with tacit knowledge, which is gathered through experience and by virtue of its nature, cannot easily be articulated or described (O’Donovan et al, 2004). For example, a criterion you give your students may read

‘…clear and logical flow of ideas incorporating well-integrated evidence that supports your argument…’,

which explicitly states the standard of expectation. Exactly what this criterion would look like in a piece of writing, however, is harder to define. Students often lack experience, so the standards of expectation have no tangible meaning to them, which is why it is important to give examples of what the standards look like (see the figure below).

What can instructors do?

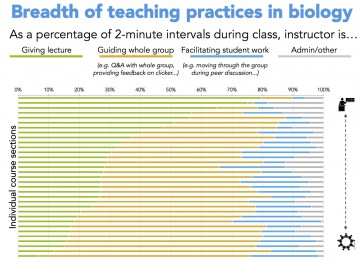

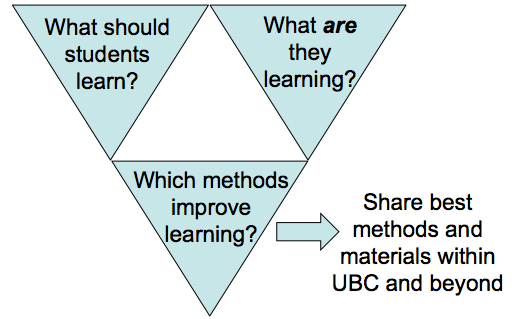

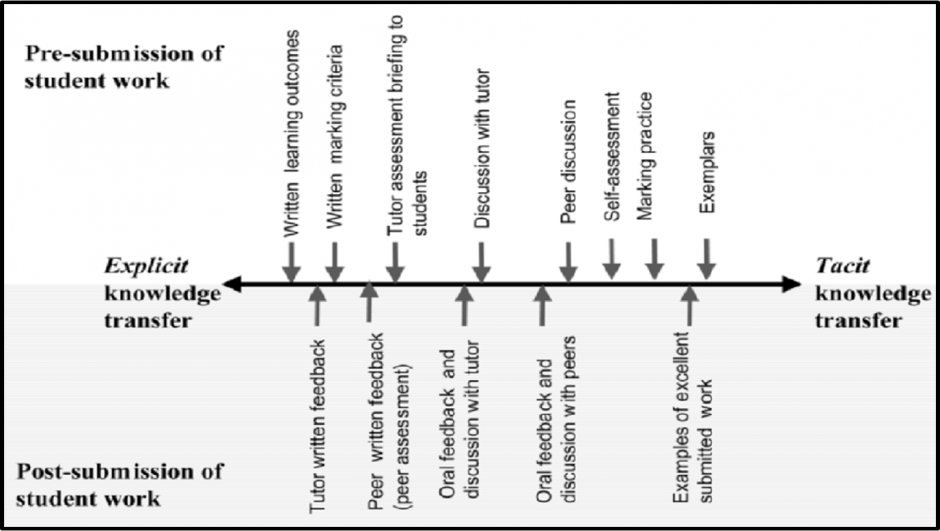

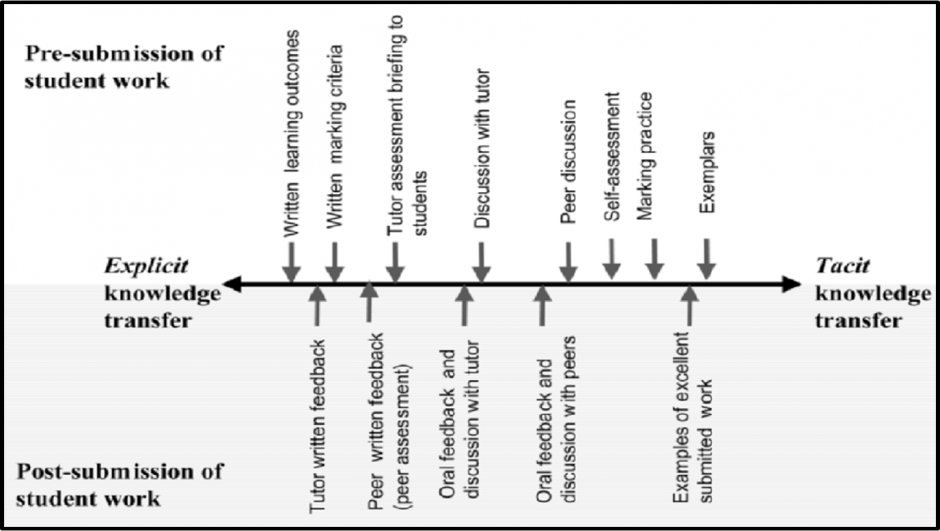

We can employ many strategies in our courses to support the transfer of knowledge regarding assessment criteria and standards to students. The figure below demonstrates how various strategies can be used both before and after students submit work, and whether the strategy supports explicit or tacit knowledge transfer.

An illustration of a spectrum of processes supporting the transfer or construction of knowledge of assessment requirements standards and criteria (O’Donovan et al. 2004).

Rubrics

It is good practice to provide students with a grading rubric for written assessments. Grading rubrics clearly (and hopefully concisely) communicate the expectations and standards for the assessment to students in an organised manner. Click here for examples of what grading rubrics can look like.

Student Grading

In addition to providing rubrics, it is even more beneficial if students have experience actually using the rubrics themselves. It has been shown that students that have participated in the grading process show significantly higher performance outcomes for similar assessments than students that have not (Rust et al, 2003). It’s possible that having students formally participate in grading experience (as described by Rust et al, 2003) is not realistic in your course, but maybe you could integrate some kind of peer feedback during the draft process.

the rubrics themselves. It has been shown that students that have participated in the grading process show significantly higher performance outcomes for similar assessments than students that have not (Rust et al, 2003). It’s possible that having students formally participate in grading experience (as described by Rust et al, 2003) is not realistic in your course, but maybe you could integrate some kind of peer feedback during the draft process.

Examples

Another simple way to promote tacit knowledge transfer is to provide examples of the kind of work you would expect from a particular type of assessment. It is most useful to provide contrasting examples that are not obviously good and poor, as this is not as useful for illustrating more subtle differences of how students could improve from a good to a very good piece of writing.

Providing exemplars to students is particularly beneficial when accompanied by a discussion about why one assignment is of higher quality than another (even better if the discussion incorporates how the grading rubric relates to the exemplars!). Using Clickers and student work in class, this approach can even be used to communicate expectations about exam question answers! (Read more about this here)

Want to chat about rubrics or other ways to increase assessment knowledge transfer? Contact us here.

Further reading on the effective use of rubrics and expert blindness:

Andrade, H. G. (2005). Teaching with rubrics: the good, the bad, and the ugly. College Teaching, 53 (1), 27-31. Link.

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons: San Fransisco.

References:

O’donovan, B., Price, M. & Rust, C. (2004) Know what I mean? Enhancing student understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teaching in Higher Education. 9(3), 325-335. Link.

Rust, C, Price, M and O’Donovan, B. (2003). Improving students’ learning by developing their understanding of assessment criteria and processes. Assessment and Evaluation, 28, 147–164. Link.

be useful and meaningful, our expectations need to be as clear as possible. The use of grading rubrics containing the criteria and standards for assessment increases consistency and accountability, and is also beneficial for communicating standards and requirements to students. But what happens when you give students ‘clear’ instructions and include a rubric, and their work is still not what you anticipate?

be useful and meaningful, our expectations need to be as clear as possible. The use of grading rubrics containing the criteria and standards for assessment increases consistency and accountability, and is also beneficial for communicating standards and requirements to students. But what happens when you give students ‘clear’ instructions and include a rubric, and their work is still not what you anticipate?

the rubrics themselves. It has been shown that students that have participated in the grading process show significantly higher performance outcomes for similar assessments than students that have not (Rust et al, 2003). It’s possible that having students formally participate in grading experience (as described by Rust et al, 2003) is not realistic in your course, but maybe you could integrate some kind of peer feedback during the draft process.

the rubrics themselves. It has been shown that students that have participated in the grading process show significantly higher performance outcomes for similar assessments than students that have not (Rust et al, 2003). It’s possible that having students formally participate in grading experience (as described by Rust et al, 2003) is not realistic in your course, but maybe you could integrate some kind of peer feedback during the draft process.